Over the past couple of decades, especially since the advent of the smartphone, there has been an increasing focus on what to do about the challenge of youth and their tech consumption. I and others have written extensively about the pitfalls associated with current usage patterns as windfall promises from tech companies remain largely unfulfilled. Even professionals, such as Sherry Turkle and others, who initially sought out to discover all of the advantages that the technology would provide, are conceding that the problems are more than we could ever imagine.

Over the past couple of decades, especially since the advent of the smartphone, there has been an increasing focus on what to do about the challenge of youth and their tech consumption. I and others have written extensively about the pitfalls associated with current usage patterns as windfall promises from tech companies remain largely unfulfilled. Even professionals, such as Sherry Turkle and others, who initially sought out to discover all of the advantages that the technology would provide, are conceding that the problems are more than we could ever imagine.

Yet despite these unforeseen challenges, we as parents find ourselves in center stage in this conundrum. It isn’t that the technology is intrinsically bad (although some of it is clearly designed for addictive, useless, and illicit purposes), but it is that the current usage patterns, especially among our youth, defy what is good for our health and well-being. The further problem is that we as adults have largely bought into the supposed tech boon, and find ourselves trying to figure out how to salvage our youth’s well-being while also saving our own.

Then, in the middle of this tech crisis, come repeated, well-intentioned recommendations from lay people and professionals alike that sound similar to this when it comes to effectively dealing with the problem:

“You should closely monitor your youth’s tech usage and also educate them about the potential dangers of using tech inappropriately.”

It seems that this advice is as ubiquitous as the apps on our youth’s smartphones. The problem is these recs frequently don’t work, and they are turning parents into cyber cops and digital detectives who are trying to figure out how to manage the other (really important) aspects of their lives.

Let me be clear. I think it is critical to thoroughly educate our youth about media/technology, and to monitor how they are using the devices. I just don’t believe this recommendation alone is either effective or sensible for a couple of main reasons.

One, if a parent really considers what it would take to “closely monitor” his or her kid’s activities on just the smartphone (not even considering multi-player online game consoles and TV/internet consumption on home devices), you start to realize that we are truly talking about a full-time job. Teen girls alone send and receive around 4,000 text messages a month. Throw in their Instagram feeds and their Facebook posts, then their Snapchat activity, and for good measure their random internet surfing, and you are going to realize that you need to hire a full-time tech monitor for this role. If you are like me, dispensable income for this position is not in the budget, and so you know what happens? Most parents simply give up or just adopt a diluted level of monitoring, and hope that their own tech monitoring apps and programs will do the job. The problem is that no matter how sophisticated these programs become, they will never approach the kind of monitoring that I (and many other parents) believe is truly the gold standard. This isn’t about thinking we can protect our youth from all potential missteps or temptations nor about discouraging appropriate levels of autonomy as they get older. Becoming more independent and making mistakes are part of learning how to become an adult. This is about being honest with ourselves as parents about what is realistic and what is not, and not creating a façade that parents and offspring alike know is not true. When this happens, it not only compromises tech integrity; it also compromises parental integrity.

Two, as I noted in a prior article, many well-intentioned recommendations not only lack realism, but are weak in substance and scientific support, especially because they assume that “well-educated” youth with “monitoring parents” will somehow create this safe vacuum that will stave off the internal and external technology threats. Although there are probably 10% of youth for which this argument will work, this simply doesn’t suffice for most of the population, and let me provide one analogy to demonstrate.

The average height for a 40-year-old female is roughly 5 feet, 4 inches tall. This is about the same average height for a 14-year-old boy, both of which possess comparable visual-motor skills. The average annual cost for full coverage car insurance for a 40-year-old (male or female) is a little under 1,400 dollars a year. Given that 14-year-olds can’t legally drive, let’s consider what the average teen male would pay annually in his first full year after getting his license. The answer is over 4,600 dollars, over three times as much as the average 40-year-old. As most of us know, teens are especially prone to traffic accidents for various reasons, many of which have to do with immature brain development that’s involved with impulse control and decision-making. In fact, teen drivers are three times more likely to be involved in fatal crashes than those 20 and older. Thus, although an average 40-year-old female and a 14-year-old boy have comparable physical size/abilities (and it would be convenient for a 14-year-old to drive), most agree that the potential negative costs (in regards to safety, financial implications, and otherwise) of a 14-year-old driving are too serious to allow him or her behind the wheel even though in just a couple of years, many will be granted this privilege.

So, I ask you. Why is our perspective towards youth and technology so wildly different? Whereas most would never offer a 14-year-old a chance to drive even with adequate training, why are we giving even much younger youth devices that absolutely overwhelm their neurological and experiential resources, and create so much potential for harm? Of course, the answer is multifaceted, and it doesn’t just involve the risk for death (which also appears to be an increased risk with smartphones). Yet the clear message is that if we are going to be successful in promoting positive tech usage, it can’t start with “monitoring” and “education.” It has to start with what we buy, sanction, and allow in our homes and schools, and what we enable to happen, both in substance and time. Otherwise, we might as well be asking our teens and young kids to manage privileges that even adults are struggling to handle, but do so with immature brains. No one is saying our young kids and teens should start driving around (or have credit cards) earlier than they are neurologically-equipped in order to prepare them for the day they will legally be able to do so. So why are we saying that our youth need their own devices long before they are able to use them responsibly?

To that question, I will end on an ironic note. There is an increasing whisper among non-native users (those of us raised before technology dominated leisure, social interactions, and education) that I am hearing when this conversation comes up. Many parents have acknowledged that they feel so fortunate to have grown up without having to deal with all the challenges that come with smartphones (and other devices), and who recognize how much unnecessary stress and hardship this is causing for their youth. I would argue that many youth recognize the stress and hardships, too, but lack the skills to not only use their tech well, and also set appropriate boundaries given how their peers “expect” them to use it, too. And so, many youth giving in to temptations that they know are not healthy because they don’t see another course. It is here where we as parents need to step in, and provide them with the guidance, boundaries, and perspective they so desperately need. If you as a parent believe that your happiness, health, and well-being would have been better in your younger years with the tech-immersive culture of today, then this contention will hold little weight. But if you are like the growing number of parents who felt that they were happier and healthier as youth when tech did not rule, then why would you not want to afford the same advantage to your offspring as you had? I for one look forward to giving my kids this gift while they are at home, and then letting them decide as well-equipped, healthy adults just how their tech usage will appear.

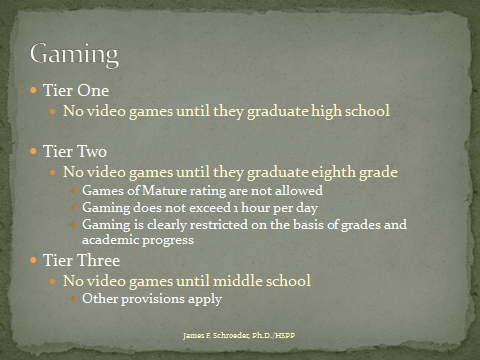

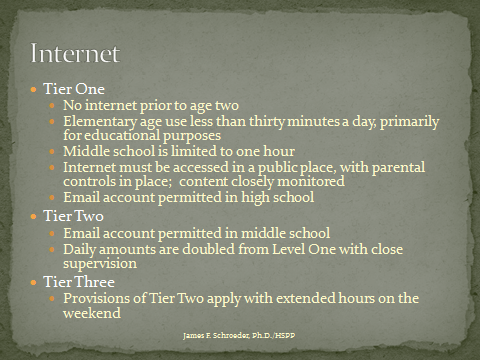

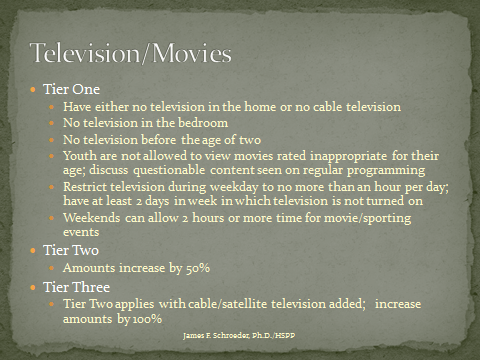

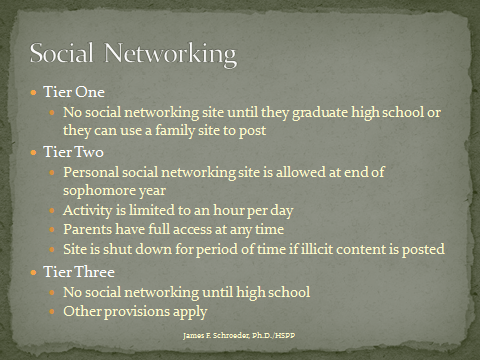

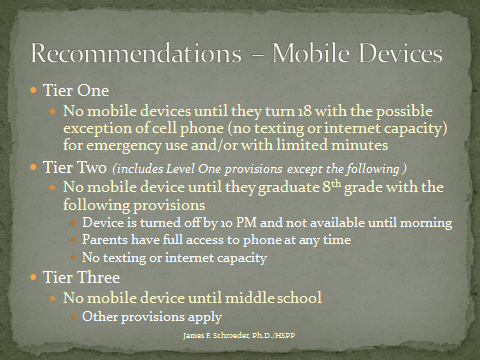

For more ideas about scientifically-oriented recommendations regarding appropriate tech usage and privileges according to age, see the included slides for different areas of devices/forums (Tier One denotes most scientifically-supported recommendations).